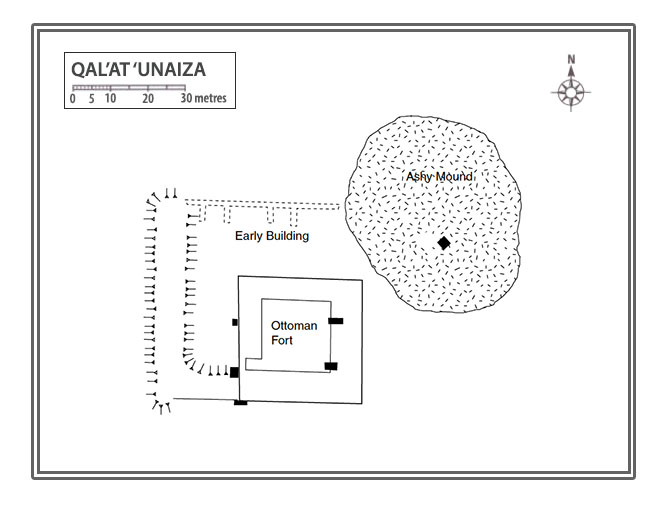

Qal’at ‘Unaiza is an archaeological site nestled on the central Jordan plateau, just a stone’s throw from the Desert Highway. Approximately 400 metres to its east lies Mahattat ‘Unaiza, an old station from the historic Hijaz railway, while the village of Hashimiyya sits 3 kilometres to its north. Dominating the surrounding landscape is the striking Jabal ‘Unaiza, an extinct volcano situated 2 kilometres west of the fort. Its presence blankets the area in a delicate layer of basalt, providing a dramatic backdrop that complements the historic character of the site.

The centrepiece of the location is an imposing Ottoman-era fort, constructed with a perfect square footprint of 28 metres by 28 metres. Its robust black basalt walls are accented with creamy white limestone quoins, although many of these have been replaced following a restoration in 2003. Towering up to 8 metres high, Qal’at ‘Unaiza stands as the largest Ottoman fort in Jordan. Interestingly, its design hints at an adaptation of a pre-existing structure, adding yet another layer of intrigue to its history.

Points of Architectural Interest

On the eastern side, facing the Desert Highway lies the gateway. It is positioned slightly north of the centre and provides a direct entry point into the fort. The south wall underwent reconstruction in October 2001, where the new foundations now extend 0.5 metres outward from the original wall’s exterior face. Back in 1986, the south wall was largely intact, showcasing three stepped crenellations and a small machicolation at the first-floor level.

The western wall, on the other hand, incorporates remnants of a much earlier building, blending history into its very structure. It is devoid of significant features beyond two small square openings visible from the first floor. Meanwhile, the northern wall still retains most of its original height, displaying the remains of at least two stepped crenellations, which provide a glimpse into the architectural detail that once defined the structure.

A Walk Through the Fort’s Interior

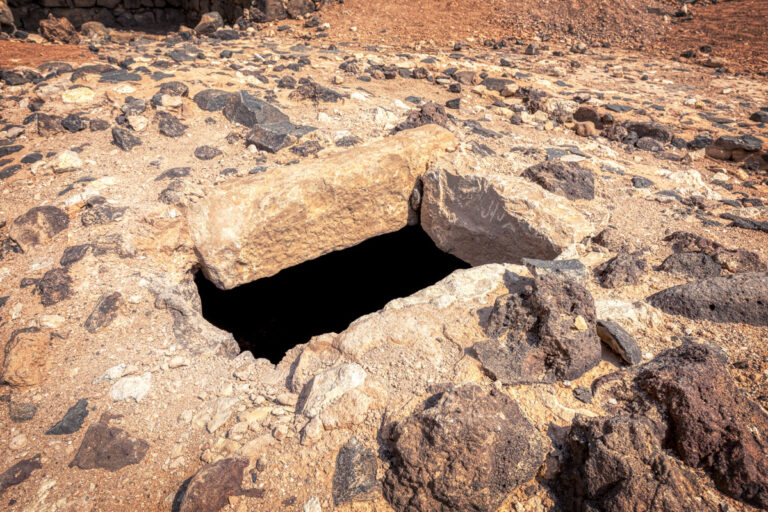

Step inside Qal’at ‘Unaiza, and you’ll find yourself in a wide, open central courtyard, designed with paved basalt cobbles set into lime mortar. It is noticeably larger than those of other Hajj forts, suggesting its unique importance. At the heart of the courtyard lies a vaulted, subterranean cistern. Accessible via a single manhole in its roof, this cistern was ingeniously fed by a drain that runs from the southwest corner of the courtyard.

Each side of the courtyard is bordered by vaulted rooms, constructed to house and support the fort’s operations. On the northern side stands a series of five small vaulted chambers, though their original facade has been replaced by a more recent, less sophisticated wall. An excavation in October 2001 uncovered the original Ottoman wall, complete with the positions of the doorways, offering insights into the precise organisation of these rooms.

The southern range comprises four almost identical rooms with rectangular layouts, barrel-vaulted ceilings, and small openings in their rear walls. The eastern range features three rooms alongside the vaulted entrance passage that leads directly into the courtyard. Intriguingly, two staircases situated on either side of this passage suggest access to an upper level, though time and erosion have left them in poor condition.

Historical Water Management

Water is central to the historical tales that the fort narrates. According to historical records, the Ottoman fort was constructed adjacent to one or more rain-fed cisterns, vital for meeting the water requirements of Hajj caravans. While the exact location of these cisterns remains debated, the most probable site is a rectangular depression to the north of the ruins of the earlier structure. This depression, devoid of basalt boulders commonly scattered across the landscape, suggests a deliberate man-made origin. Supporting this theory, a wide channel from the west leads directly into the depression, indicating a functional water collection system. It’s also conceivable that stone linings from the cistern were removed and repurposed during the railway station’s construction.

A Glimpse into History

The rich heritage and striking architectural features of Qal’at ‘Unaiza offer visitors a chance to step back into a pivotal era of Middle Eastern history. Its layers of volcanic basalt, Ottoman design, and hidden stories of pre-existing structures whisper tales of resilience in the face of time and the elements. Whether it served as a fortification, a resting place for Hajj pilgrims, or a command post, Qal’at ‘Unaiza stands today as a testament to the ingenuity and craftsmanship of its creators.

With its awe-inspiring surroundings and unique historical significance, this fort is more than just a relic; it is a living canvas that continues to tell its story, stone by stone.

Key Moments in History

2nd Century: Possible establishment of a Roman caravanserai linked to the Via Militaris and the nearby fort at Dajaniya.

16th Century: Reappearance in historical records; Khan ‘Unaiza mentioned in Ottoman texts by 1563.

Key Moments in History

2nd Century: Possible establishment of a Roman caravanserai linked to the Via Militaris and the nearby fort at Dajaniya.

16th Century: Reappearance in historical records; Khan ‘Unaiza mentioned in Ottoman texts by 1563.

1576: Construction of the Ottoman fort, attributed to Sulayman Pasha, alongside a similar project at Hadiya.

1709: Murtarda ibn ‘Alawan describes it as a spacious, well-maintained structure owned by the Bani ‘Idha.

Early 19th Century: Found in disrepair by Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha’s engineers and deemed unsuitable for pilgrims.

1896: Traveler Gray Hill visits the site, noting its picturesque setting near Jabal ‘Unaiza.

1897: German scholars Brünnow and von Domaszewski document a functional walled cistern.

1916: The site becomes part of a 36-kilometre Hijaz railway branch line to Shobek, aiding fuel transport.

1972: Recognized as an Antiquities Site by the Jordanian Antiquities Department.

1990s: Dana Archaeological Survey identifies pre-Ottoman remnants and confirms its role as a major classical site.