Mshash, an expansive Umayyad settlement, once flourished as a grand city in the vast desert landscape, though today it lies in near ruin. Perched on the edge of Wadi Mshash, it blends seamlessly into its surroundings, making it almost invisible at first glance. Despite its current state, Mshash boasts an impressive array of features, most notably a significant number of hydraulic installations—a rare testament to engineering ingenuity. These include reservoirs, cisterns, and dams, both near the settlement and further afield, underlining the site’s historical importance in water management.

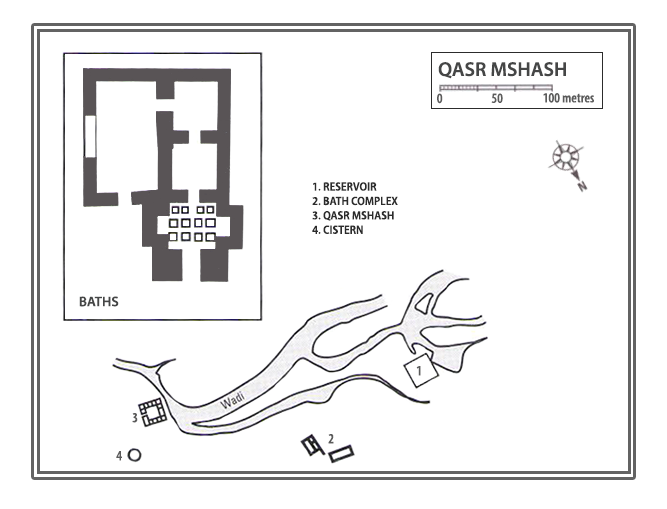

The Qasr Mshash site spans an impressive 2 square kilometres and is divided into two principal areas, set 1.5 km apart. Preliminary surveys and geophysical research suggest that the core of the settlement likely served as a vital caravan halt. This core area includes a striking caravanserai-like building, a bathhouse, and a large reservoir partially buried in the desert sands. Only remnants, such as the southern wall and a plastered settling tank, which extends towards the west, are visible today. Surrounding this central hub are smaller domestic structures, forming a modest settlement that likely catered to the sustenance and restocking needs of passing caravans.

Water was the lifeblood of Mshash, as evidenced by its intelligently designed supply systems. Preliminary investigations reveal that the settlement relied solely on winter rains, which channelled through small streamlets from the north into the Wadi. Ingeniously, the natural slope of the land allowed these streams to flow into cisterns and reservoirs, providing an easily controllable water source.

While the significantly larger Wadi Mshash offered a potential water source, its lower elevation complicated access, requiring mechanisms such as water wheels or lifts—none of which have been discovered so far. Further research is necessary to reconstruct the conduits and fully understand the water supply methodology. At the heart of Mshash lies a modest yet fascinating structure—a compact 26-square-metre building featuring 13 rooms around a central courtyard, with an entrance oriented to the east. This structure served as a crucial halt for caravans travelling between Amman (then Philadelphia) and Wadi Sirhan. Its strategic location connects it with other nearby Desert Castles such as Qasr Al-Muwaqqar, Qasr Kharana, and the UNESCO-listed Qasr Amra, all situated 15 to 20 kilometres apart. These sites collectively reveal a network that sustained and safeguarded travellers through the harsh desert terrain.

Since 2011, the Orient Department of the German Archaeological Institute has partnered with Jordan’s Department of Antiquities to further our understanding of Mshash. Their collaborative efforts aim to meticulously document all archaeological sites within a 10-kilometre radius of the settlement, draft an updated and comprehensive plan of Mshash, and create an intricate 3D model of the site. Equally important are their ongoing investigations into the settlement’s water supply systems, which promise to unveil the innovative resource management techniques that made life in this arid region possible.

Mshash stands today as a testament to human adaptability and ingenuity, carrying echoes of an era when it was a vital node for travellers, traders, and settlers navigating the Umayyad desert network. It invites us to marvel at its remnants and reflect on the resourcefulness of those who built and thrived within its walls.

Key Moments in History

8th Century AD: Qasr Mshash was constructed during the Umayyad period as a strategic caravan station and rest stop along trade routes, connecting Amman to Wadi Sirhan.

Ceramic Evidence (3rd Century AD): Prior use of the site, suggested by Roman-era ceramic finds, indicated its significance before becoming part of the Umayyad network.

Key Moments in History

8th Century AD: Qasr Mshash was constructed during the Umayyad period as a strategic caravan station and rest stop along trade routes, connecting Amman to Wadi Sirhan.

Ceramic Evidence (3rd Century AD): Prior use of the site, suggested by Roman-era ceramic finds, indicated its significance before becoming part of the Umayyad network.

Functionality: The settlement grew into a self-sustaining complex with hydraulic systems (cisterns, reservoirs) and structures for travellers, including baths, a caravanserai-like building, and domestic units.

Medieval Arab Accounts: Chroniclers noted the site’s role in the Umayyad postal system and as a node on regional trade routes.

1901: A. Musil provided the first brief description of the site during his travels.

1939: A. Stein extensively documented the Qasr in the broader context of his archaeological projects.

1980s Excavations: G. Bisheh brought the site into focus with detailed studies of the Qasr, baths, and cisterns, enhancing understanding of its layout and use.

2000s Modern Research: Since 2011, collaborative work between the German Archaeological Institute and Jordan’s Department of Antiquities has focused on mapping, preserving, and modelling the site, with an emphasis on its advanced water supply system.

Present Day: Qasr Mshash remains an important archaeological and historical site, revealing insights into Umayyad ingenuity and desert adaptation.