Seven kilometres past Qasr Deir Al Kinn, the enormous black basalt walls of Jawa rise dramatically from a rocky ledge beside the Wadi Rajil. It’s a sight both awe-inspiring and mysterious—a remnant of an ancient civilisation whose story is shrouded in enigma. Jawa’s construction was a colossal feat, yet the people who built this town, their origins unknown, abandoned it after fewer than 500 years. Among its marvels is the oldest known dam in the world, dating back to 3000 BC—part of an ingenious water supply network that once sustained this desert settlement.

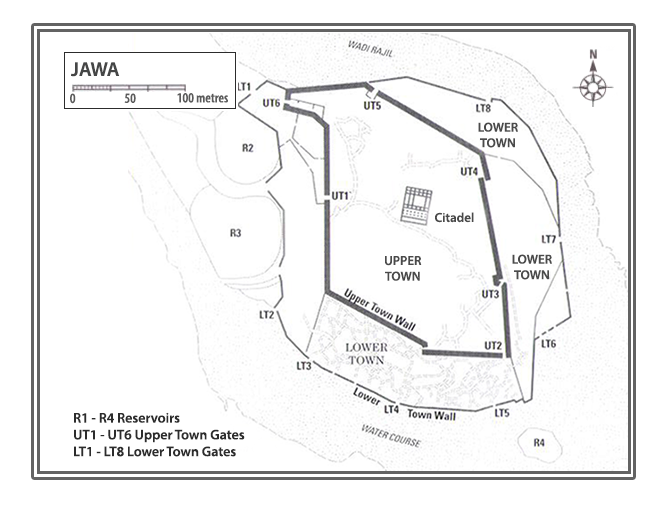

To begin your exploration of this striking site, ascend the ridge to the northwest. Passing by an ancient reservoir, now repurposed, you’ll arrive at the crest of the hill where Jawa’s upper and lower towns unfurl before you. Both were encircled by towering walls of roughly-hewn basalt—fortified barriers that spoke of protection and resourcefulness. The upper fortifications, built first, still stand a proud 6 metres high in some places, hinting at the impressive engineering skills of their builders.

The lower town came later, likely evolving from a temporary labour camp for the workers tasked with constructing the upper fortress. Divided into three sectors, it sprawls within its own enclosing wall, which lacks the same strength but boasts remarkable gates. The entire site, in fact, offers a staggering number of gates—at least six in the upper town and eight in the lower—far more than is typical of prehistoric settlements in the region. The craftsmanship is evident, particularly at the south gate of the lower town, where you’ll see two internal chambers and an arrangement of doors, including one double-leaf and two singles. The gate’s flanking walls reveal an early example of true casemate construction, an architectural style that wouldn’t become common in the Near East for over a thousand years.

Angular, irregular houses fill both the upper and lower towns, creating a labyrinth of stone foundations and mud-brick structures. Many are partially subterranean, with roofs supported by oak beams, likely sourced from the Jabal Druze, layered with reeds and mud. Behind the main gate of the upper town, excavated homes reveal remnants of plastered walls and mus floors, offering a glimpse into the daily lives of Jawa’s inhabitants.

At the centre of the upper town stands the Citadel, an imposing rectangular structure divided into cells and transverse corridors. Remarkably, some of its basalt roof beams remain in place, and evidence of an upper storey lingers. Surrounding the Citadel are outbuildings thought to have been part of a Middle Bronze Age caravanserai—a bustling waypoint on the trading routes connecting Syria, Mesopotamia, and Arabia.

But perhaps the most extraordinary achievement of the Jawaites lies in hydrology. Situated in an arid landscape where springs are rare and groundwater elusive, they mastered the art of harnessing winter rains. Over 8 kilometres of intricately designed canals, diversion weirs, dams, and reservoirs worked seamlessly to collect and store water. At three key points, rainwater was channelled into canals that flowed towards circular reservoirs, several of which can still be seen today, weathered yet steadfast reminders of their unparalleled ingenuity.

Every stone, wall, and structure in Jawa whispers a story of resilience, creativity, and adaptation. It’s a site that captivates not just with its scale and history but with the mysteries it still holds, inviting visitors to walk its ancient paths and imagine a world long past.

Key Moments in History

Early Construction in the Early Bronze Age (circa 4th Millennium BCE): The settlement of Jawa emerged as one of the earliest planned towns in the arid regions of Jordan, showcasing advanced urban design.

Innovative Water Management System: Jawa's inhabitants built an advanced system of reservoirs, channels, and dams to collect and store water, an incredible feat given the challenging desert conditions.

Key Moments in History

Early Construction in the Early Bronze Age (circa 4th Millennium BCE): The settlement of Jawa emerged as one of the earliest planned towns in the arid regions of Jordan, showcasing advanced urban design.

Innovative Water Management System: Jawa's inhabitants built an advanced system of reservoirs, channels, and dams to collect and store water, an incredible feat given the challenging desert conditions.

Fortification and Defense: The town was protected by robust walls and defensive structures, highlighting the importance of security in an era of frequent conflicts and raids.

Economic and Trade Role: Jawa likely served as a hub for trade and agriculture, connecting nomadic and settled communities in the region with standardised storage and distribution of goods.

Abandonment and Decline: The settlement was eventually deserted, possibly due to prolonged droughts or resource depletion, leaving behind its impressive ruins as a testimony to its early innovation.

Modern Rediscovery: Archaeological excavations in the 20th century unveiled Jawa’s sophisticated urban planning and water systems, offering invaluable insights into Bronze Age engineering.

Recognition as a Technological Milestone: Jawa is now celebrated as a symbol of human ingenuity and resourcefulness, inspiring further research into how ancient civilisations adapted to harsh environments.