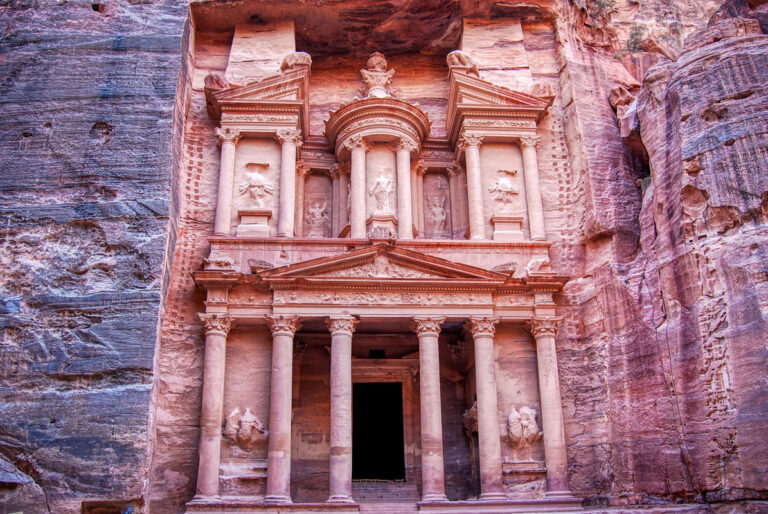

Hidden among the rock-cut monuments of southern Jordan, archaeologists have discovered a simple yet fascinating relic of daily life in the Nabataean world — stone-carved Mancala boards. These small, rectangular slabs or panels with rows of shallow depressions reveal a very human side to a civilisation best known for grand temples, tombs, and water systems.

A Game of Stones and Strategy

Mancala, one of the oldest known board games in human history, is based on a deceptively simple concept: players move small stones, seeds, or pebbles around a board’s depressions to capture or accumulate pieces. Versions of the game have been played across Africa, Arabia, and Asia for millennia.

In the Nabataean context, boards were discovered at sites such as Petra, Little Petra (Siq al-Barid), and Sela, carved directly into rock surfaces, stairways, or flat courtyard stones. Typically, the boards feature two parallel rows of six to seven small cup-like holes, sometimes with a larger storage hole at either end — a design nearly identical to the modern Mancala or “Al-qirkat” games still played in parts of the Middle East today.

From Traders to Players

The Nabataeans, famous for their control of desert trade routes and mastery of water conservation, lived lives that balanced commerce, defence, and leisure. These Mancala boards likely provided entertainment and mental stimulation during long pauses in travel or trade.

Archaeologists believe the boards were used by caravan guards, merchants, or temple visitors, offering a pastime as they rested in caravanserais or guard posts. Their placement — near public courtyards, steps, or shaded rock faces — supports the idea of a social game, played communally while exchanging news or awaiting the next caravan.

Game of Empires and Eternity

While the Nabataeans flourished from the 4th century BCE to the 1st century CE, the presence of Mancala boards connects them to a much broader human tradition. Similar stone-carved boards have been found in ancient Egypt, Ethiopia, Yemen, and the Arabian Peninsula, underscoring shared cultural threads across trade routes.

In Jordan, the boards are not only historical curiosities but tangible expressions of the Nabataeans’ daily rhythm — moments of recreation amidst monumental landscapes. The game’s endurance across millennia speaks to its universal appeal: strategy, patience, and chance combined in a handful of carved holes and pebbles.

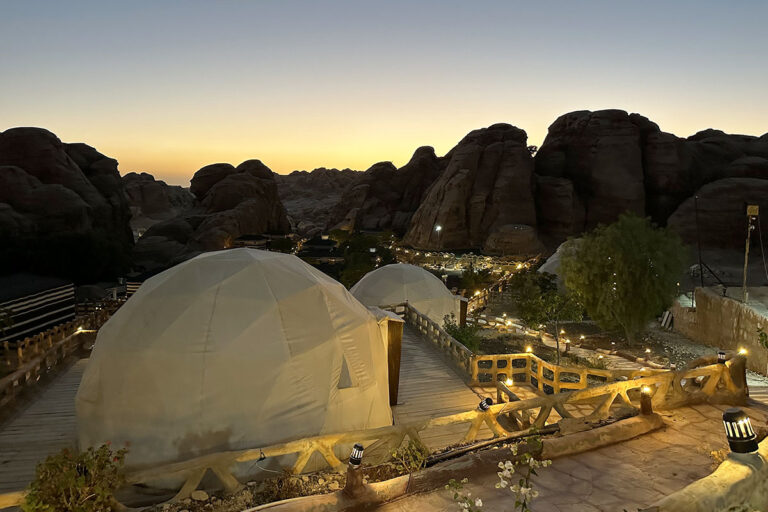

Visiting the Sites

Today, visitors exploring Little Petra or Sela can still see these ancient game boards etched into the sandstone. Standing before them, it’s easy to imagine Nabataean traders passing the time as the desert sun dipped low, each move on the board echoing a blend of competition, camaraderie, and contemplation that transcends centuries.

A Legacy of Play

The discovery of the Nabataean Mancala boards reminds us that even in a world of monumental architecture and vast trade networks, people have always sought connection and entertainment. These humble carvings are among the most human artefacts left behind — proof that the same urge to play, to think, and to share persists unchanged across time and empires.